Story by Joshinkan Germany, October 2023. You can find the images at the end of the blog (some images are taken from video frames with lower resolution)

Indonesian traffic is ruled by scooters. Everywhere you need to go, you wave for a scooter taxi. If you are lucky, you get a helmet. You better hang on to the side handle during the ride. The skilled riders zigzagging through the horrific (left-hand) traffic, scooting into the other lane to skip cars. Most riders wear masks, not for the pandemic, but because of the pollution and dusty roads in overcrowded cities on Bali. Having had the prospect to travel to Indonesia, I did not want to miss the opportunity to look at the local martial arts of Pencak Silat. I practice Isshinryu-Karate and Tokushinryu-Kobudo and had only little exposure to Bruneian Silat (SSBD). My specific interest in going to Bali was to learn something about the traditional aspects of the local arts and the integration of traditional weapons into their system.

I had planned my visit to a local Pencak Silat “Padepokan”(which means “dojo”) a few months in advance. However, it was not easy getting in contact with a local school. They probably get a lot of requests and don’t answer until the time is due. It was just until a few days before my arrival on Bali that I received a message from Mr Adi Wirawan, the head coach of a regional Silat school. Master Adi invited me to visit his school and practice the art of Bakti Negara in Badung, about 1 hour north of Denpasar. I booked a place in the area, which was far away from the tourist beaches and holiday villas.

I have summarized my three days of training in Bakti Negara below. In addition, I provide insight to Bakti Negara, based on several interviews with local masters and hope this is also of interest to the martial arts community in Europe.

Training day 1

Mr Adi suggested meeting on Monday evening. I arrived in Ranting, Badung region after a 20-minutes scooter ride through dense traffic. I brought my Karate pants and a T-shirt, hoping for some introduction to Bakti Negara. The school waslocated at the teacher’s private ground, attached to his house, which is a combined area of living space and temple. A steep driveway leads to the property. I saw a Ying-Yang ornament laid in stone on the ground next to a small, gated Hindu temple which is meant to protect the training place and its students (see also image 7). The gate had a variety of ornaments, emblazed in the middle I recognized a golden Swastika, which in the Hindu-Culture (also in Buddhism) represents different aspects such as core Hindu scripture, four seasons of the year, good fortune, or cycle of life – just to mention a few.

Master Adi was still at work when I arrived. I entered a sheltered open area with green tatamis and a roof made of corrugated iron sheets. There was only little space between the grey painted stone walls and the roof, allowing a small stripe of daylight to shine into the Padepokan. The floor wascovered with a square of 6×6 meters of tatamis, which looked very much used. A metal frame with monkey bars and racks for boxing sacks was installed at the left-hand side of the shelter. A pile of old car tires purposed for training and a dozen of pads and other equipment were stacked in the corner. The front part of the Padepokan had two large mirrors and a concrete seating area with the words “Bakti Negara” laid in stone. Not to forget, there was also a small toilet room with a ground floor WC and a shower.

Two SUVs were parked right on the edge of the tatami. At18:30, dusk was approaching fast, my phone suggesting it is about 30 degrees and 92 % humidity! So, this was an outdoor training center with minimum comfort. Nothing for spoiled kids, I thought.

A young man in his twenties and a younger lady practicedalready in full protective gear on the green tatami floor (see image 2). Despite the heat, the young woman wore tracksuitsand body protector, but no head protection, or gloves. The young man showed his partner take down drills from standing positions and sweeps. Few punches, catching the leg after a kick and taking the partner down. Again, and again.

I sat on the concrete bench and watched the training for a while as two scooters raced into the shelter and two young men in black Pencak Silat outfit got off their motorbikes. One of them introduced himself as Arya, the son of Master Adi. The other one was Radith, also a student at the local place.

Arya informed me that his father will be late from office, and I should make myself home. The boys asked me a couple of questions in English. I learned that both are Police trainees and delegated to the national Bali Silat team, preparing for the national championships in November. Arya showed me the huge banner on the wall with his image after winning the South-East-Asia Junior Games in the Pencak Silat fighting division in 2019. He certainly must be the pride of the family, following his father’s footsteps. It turned out that the young woman who trained with a partner when I arrived, was Arya’s sister Tasya, also a talent in Bakti Negara.

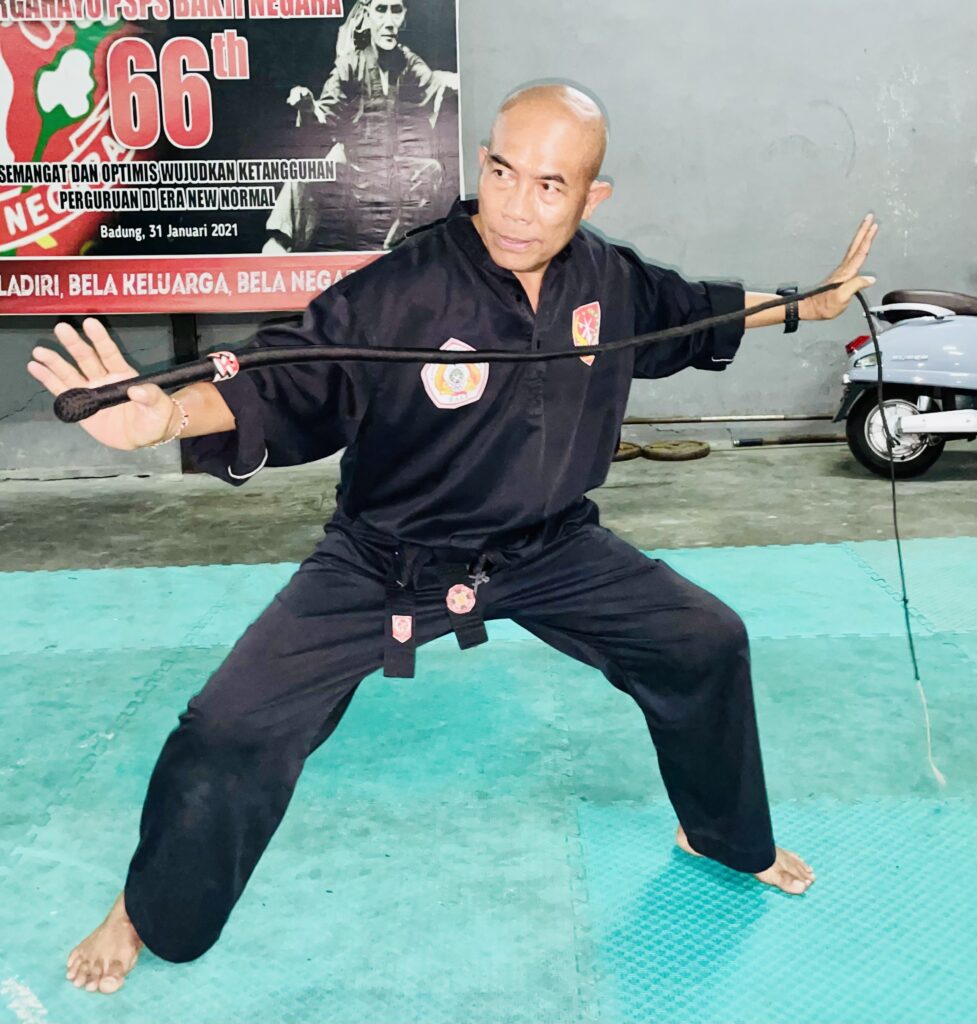

Meanwhile another scooter drove into the hallway. The men also wore a black traditional Pencak Silat uniform with a black belt. He was holding on to a long bamboo stick with a red-white ribbon attached – the colors of the Indonesian national flag. When he took off the helmet, I saw a bald gentleman in his sixties with a friendly face and well-trained appearance walking towards me. This was Mr Oka Ajik, andone of the senior coaches and trainers of Bakti Negara (see image 4). Mr Oka used to work in the tourist industry and had travelled the world. He had a good command of the English language, which made it easy for me to introduce myself and thank for the invitation to learn something about Balinese traditional martial arts.

Eventually, Mr Adi also arrived from work – with one of his electric scooters. Eventually we got to meet in person. Mr Adi began with Bakti Negara about 36 years ago, when he was 9 years old (see image 3).

He quickly changed into the traditional Pencak Silat uniform, and we began with the training. Every training starts with an etiquette or prayer, similar to the Japanese practice, with closed eyes and bowing into the corner of the masters’ portraits. This was followed by warm-up; similar routine as we practice in Karate to get body, muscles, and joints flexible. For stretching, flexing and warm-up, every movement is repeated twice before switching to the other side or exercise.

Bakti Negara also has “kihon” implemented. A set of techniques, such as double punch to the middle, punch to the groin (all in one sequence), inside block, outside block, backfist. There is no single punch to the face from high a stance, due to the fighting rules and the understanding, the fighter would throw middle punches and the opponent, when hit would lower his stance, which brings the neck and face into the target zone.

We trained kicks, such as the “Cobra-kick”, which is a unique technique. The aim of the sequence was to catch a karate-kick like Mawashi Geri, which was easy enough, followed by a sweep or other forms of take down. The latter takes some technical skills. The cobra-kick works from the outside with an outwards hip (opening) rotation and high-up knee to kick to the chest of the opponent. I have never kicked that way, but it feels effective and makes catching the leg much more difficult.

My host asked me to show some karate routines, which gave me the opportunity to introduce a specific Isshinryu flow, which I learned from Sensei Lars Andersen from Copenhagen. The young athletes showed great interest and had been excited to learn something new. This gave me the possibility to explain more about Karate and how it is practiced in Europe. After that we continued with sand sack training, kicking, and punching with haymakers and uppercuts. Now I was drenched in sweat. The humidity in October was incredible high and I was definitely not used to it(see image 5).

At the end of the training Master Adi’s lovely wife, MsHanas, offered snacks and lemonade. I used the break to inquire more about the weapons of Bakti Negara and the symbolics of their crest.

Later on, Arya volunteered to show me a form with the long stick and with Golok, the machete, or as it appears, a very long, solid knife. This performance was beautiful and gracious. I tested the handling of the Golok and tried to move the blade in a safe way. I was told to think about Nunchaku, which was a good tip. However, rolling the long knife through the fingers and the hand will take decent time to practice.

The training finished about 21:00 hrs. Ms Hanas had organized a scooter to take me home and insisted on paying for the ride.

Training day 2

On the next day, I arrived already at 18:00 to prepare myself and go through some routines of the previous training. An old gentlemen close to his 80s, walked into the training place, wearing traditional clothes, a sarong, and slippers, but no shirt. I greeted him but he did not speak any English. He looked like someone with a great sense of humor. He then only smiled and watched my activities. Now I had no excuse to train despite the heat and humidity. Later it turned out that the men being Master Adi’s father.

After a short while, Ms Hanas came to welcome me. She invited me to see their house and learn about their tradition. I was guided through the property gate into the beautiful house with a white stone floor and high ceilings. Ms Hanas showed me the backyard where I noticed an elevated area also with white stone floor, which is the family gathering place. In addition, there was another wooden platform, built in a traditional fashion with carved poles and a temple-inspired roof. This open-air space serves as a ceremonial place. In case a family member would pass away; the body would be bedded there in a certain way for visitors to come to show their gratitude and respect for the deceased before cremation takes place.

The yard also had roof top temple to worship the gods and commemorate the ancestors. It is deeply rooted into Hindu-tradition, that every real estate must have its own temple and a ceremonial family place for the funerals of family members. The ashes of the ancestors are placed inside such private temple. The two red brick stone temples were about 3-4 meters high and 1 meter wide like a miniature tower, with golden roofs and stone inlays. Small colorful doors with golden frames were attached (see example image 6). Plates with incense cones, flowers and symbolic offerings had been placed at the bottom of the temple. I was flabbergasted and overwhelmed by the place and the open-minded introduction to all these religious aspects of their private life.

In one corner of the yard, I spotted a massive stone wall with the symbols of Bakti Negara: a sword, a trident knife (like Japanese Sai), and a bamboo spear, framed by cotton and rice paddy branches on each side. These are the three symbolic weapons of Bakti Negara, the Trisula (Sai), often seen with Shiva monuments; the Bamboo spear, symbolizing the typical essay accessible farmers weapon, and last but not least the machete, a regular working tool. The chain under the symbol stands for independence from oppression and the rice and cotton leaves demonstrates prosperity (see image 1).

Everyone visiting such a place will be enchanted by the mystic charm of the aesthetically architecture of Balinese traditional houses. As a first-time visitor to a private Balinese house I am carried away by so many impressions and insight to the traditional and religious life of the family. When I travelled through the streets, I then recognized all the private house temples sticking out behind the walls. To put this in perspective: The price of a temple to be build is the same as the house itself.

Right on time, Arya and his sister Tasya arrived. We practiced the Cobra-Kick again and did some pad work. Arya definitely did not spare his sister. She also showed some great skills. Later, after Master Oka arrived on his scooter, we intensified the sweep work. Scissor sweeps are common in Bakti Negara. The action can start on the floor, attacking the rear foot to unbalance the opponent, but it can also be above the knee, the waist or for some athletic action, high up to the neck to get the opponent rolling or spinning. Arya used a human size dummy for the training. Master Oka holding the dummy and Arya would snap it with a slide-jump, making the dummy slamming to the ground, followed by a second spin, using the momentum of action. This looked smooth and effortless. However, when I tried the exercise, I noticed how difficult it is to focus on the continues spin after the initial part of the take down sequence, which is the cherry on the cake for this flow. I got excited when Master Oka brought out the Golok again and we practiced basics, which in Kobudo would translate to the eight corners, slicing in all directions, finish with a stab to the middle. The blade is only sharp on one side which allows one to attach it to the forearm, hiding it from the view of the opponent, similar to the “Gyaku Mochi” position of the Sai in Kobudo.

I noticed a pattern across the practice of weapon forms in Silatwith pointed weapons (Golok, Kris). The person would drop into a lotus seat position and stab sideways under your armpitfor a hidden attack. When practicing spinning into the lotus seat, I was afraid to look like a spider trying ice-skating. I was sure, the grandfather had some fun watching me. Anyway, the Golok and Kris practice was a lot of fun and new to me, since the Kobudo-system, which I practice, does not include a knife or sword. The closest weapon from Tokushinryu Kobudo to this application would be Rochin (Tinbe) and Kama, the sharp sickle. By the way, the Balinese sickle in Bakti Negara is curved like a moon and has a shorter grip.

Master Oka showed me some techniques with the rattan stick, called Toya. I followed the drills which are much more fluent in Bakti Negara due to the light weight of the weapon compared to the Kobudo oak Bo. After a while, Mr Oka produced the most stunning and unexpected weapon – a long black whip, the “Pecut” (see image 8). I got to see it in action and was frightened about the sound and power of this long-range weapon.

Master Adi could not join the training due to the dense traffic from his workplace at the airport. However, he and Master Oka remained available for interview questions.

Towards the end of this intense training day, Ms Hanas brought huge coconuts with bamboo straw and a plate withfried sweet potatoes, which came in handy after the exhausting training under the boiling hot shelter. We all sat at the stone bench chatting away and enjoying great company. Mr Oka had also filmed the actions during the training. They shared the videos with their peer groups since the message had spread that a foreigner came all the way from Europe to Banting to learn about Bakti Negara. I felt very welcome.

I thought, this was the right moment to handover the gifts I brought. I presented Master Adi, Master Oka and the Arya with a Joshinkan Kobudo T-shirt, some patches, and a book. Not long after, Master Adi presented me with a t-shirt in return, with the Bakti-Negara logo and the sign “Denpasar Fighter”. Fantastic!

Meanwhile, Ms Hanas had called (and again paid for!) my scooter Taxi. I hurried to finish my food. Mr Adi showed me how to handle the coconut and get to the meat through the small hole on the top. He said that’s like an isotonic drink, good for sport. I got few more potatoes on the way and left the training center, looking forward to getting a shower and a dip in the pool of the resort. By the time I was back, it was about 10 p.m. Never slept better.

Training day 3

We had not agreed in advance about the number of trainings or how many days I could spent in Ranting training center. However, Master Adi offered me to come as often and long as I wanted, free of any charge, since this is not the philosophy of Bakti Negara.

So, I attended another day, especially to continue with the conversation about Bakti Negara. My scooter taxi dropped me at 6 p.m. There was the student from the first day, working out with weights and CrossFit exercises. No doubt, he was fit as a fiddle. He left shortly before Arya and his friend Raditharrived.

Mom, grandpa, and another friend also came by to take pictures and watch the training. For the warmup, Arya asked me to show some Karate techniques. I introduced a flow of lock techniques, which originate from Isshinryu Sensei Lars Andersen, inspired by kata applications and also modern submissions techniques, and chokes. I noticed that my junior training partners had little experience with hand wrist manipulation and neck chokes, which is understandable since they primarily focus on performance and competition. However, they had great fun as well as the spectators on the side of the tatami.

Mr Oka arrived at the scene, which gave me the opportunity to ask to take some photos and film a short interview about the meaning of the symbolics of Bakti Negara. The junior athletes agreed to film some of their techniques and applications. They put on the kit and demonstrated the competition rules, supported my Master Oka as referee. I learned that rules had changed for the Indonesian Silat Federation to make the fighting more attractive and introduced different point systems over the years. This sounds familiar to Karate practitioners. Silat is practiced in many South-East-Asian countries and had spread over the time to Europe, Brazil, the US, probably with migration waves of Indonesians. Despite the internationalization, the Indonesian association has little interest in any Olympic recognition such as Karate-Federations had.

The Karate competitions during Olympia 2021 (2022) in Japan did not remain unnoticed in Indonesia. However, there are no ambitions to uplift Pencak Silat to an Olympic discipline. When travelling through the country, especially in Denpasar, I saw a few karate schools and a good number of students in full karat uniform flying past on their scooters on the way to the training, I supposed. So, few karate schools are also available on Bali.

Anyway, Master Adi arrived from work, and we continued with discussions and interviews about the structure of Bakti Negara on Bali. The implementation into school, university, police, and military provides broad access to students and support. I probably asked too many questions due to my lack of knowledge about Pencak Silat and Bakti Negara. I hope not to upset my hosts. It actually reminded me of Japan, when we visited our masters and had all kind of questions. You all know that there is often a standard answer, especially at mainland Japan. However, here on Bali I also tried to thread carefully, not to overwhelm or challenge my hosts. But I got the impression this was not an issue and Master Adi and Master Oka patiently answered my questions.

In addition, Arya was asked by his father to explain and demonstrate the performance requirements for weapon forms. If I understood this correctly, the athlete must perform 3 formsafter another, beginning with open hands, followed by twoweapons. Arya took position on the sideline corner of the tatami. His name and the school are called out loud. He was holding the Golok machete in the right hand and the long rattan stick in the other hand behind his back (see image 9). The end of the rattan stick was only visible a couple of inches behind his head. Then he marched into the middle of the sideline, followed by a quick 90-degrees turn, facing the center and then walked to the last row of the tatami, where he put down the stick and Golok. Now a ceremonial set of movements followed, referred to as “dance”. Arya then began the open hand form. I saw an elegant “kata” with quick moves, kicks, and jumps. At the end he arrived close to the weapons in a lotus seat position. He then took the Golok to continue without break. I could hear the special breathing, like hissing-sounds; there is no kiai, though. After a minute or so, the Golok was exchanged with the rattan stick, which cuts the air with a buzzing sound and two-three snappy hits to the floor with a loud bang echoing under the metal roof shelter(see image 11). The performance finishes again in the lotus seat (see image 10). Then he performed the standard etiquette. This completed a 4-minutes competition form! I wasimpressed and can only imagine how exhausting this wasunder these conditions. After more chatting and explanations, we took a seat and Ms Hanas offered us coconuts and snacks. We took some final photos.

I changed my soaked T-shirt. The soles of my feet were pitch-black from the dusted tatami. The local scooter taxi arrived,and it was time to say goodbye. I was taken away by their hospitality and friendship offered to a stranger who walked in as curious tourist two days ago and will leave as a friend – like brothers (and sisters) in arms. I enjoyed the open-minded and friendly atmosphere and asked myself how we at home would embrace someone coming by, disturbing the routine of preparation for an important championship, and asking hundreds of questions, and even paying for transportation. …. Exactly!

History and roots of Bakti Negara

Pencak Silat, in the Javanese culture means “Martial Arts” and is the umbrella for all regional self-defense arts. The historical roots go way back to the 8th century. There is almost an uncountable number of Pencak Silat styles in Indonesia and South-East-Asia, ranging up to 1000 variations, which also include different sets of weapons.

Bakti Negara as one of the Pencak Silat forms translates into “Loyalty to the Nation”. Bakti Negara is a regional school that was established as a style in 1955 by a group of Balinese war heroes. The element of warriors and their involvement in the post-colonial resistance and the national independence movement 1945-1949 against the Dutch Empire is of utmost importance to understand the role of Bakti Negara and other Pencak Silat styles on Indonesian Islands.

The Silat schools see themselves as a social movement, supporting society. The Bakti Negara motto is enshrined in their statutes as: 1. Self-defense, 2. Defense and Protection of the family, and 3. Protection of the country (see image 12). This demonstrates the strong relation between government and Silat. Police, public administration, and army are strong supporters of Pencak Silat.

On Bali, Pencak Silat is even more popular than soccer, which ranks on number 2 of sports activities amongst young people. This has also to do with the fact that the costs for football equipment is high for a family, earning substandard wages, and there are almost no football fields available. Also, forget street football at such densely populated areas like Indonesia with 250 million people. So, Bakti Negara, like other Silatstyles, offers free access to training. The Bakti Negara school in Badung/Ranting teaches classes every night for up to 35 participants from 8 years up to university classes. Athlete students can receive training under very good conditions in Denpasar at special facilities.

Competition

My first lesson in Bakti Negara focused on the sportive side of the system. The two junior athletes explained the rules for fighting. They fight for 3 rounds fighting á 2 minutes. A correct punch to the body (protected areas) would be 1 point. 2 points are given for a kick to the protected areas, and 3 points for a take down. The fighters don’t use head protector, and no gloves. The protective gear is Shin protector and body protector (like in Taekwondo), as well as groin cup. Punches or kicks to the head are not allowed. The style of fighting looks like moving into positions, certainly no jumping like in Karate.

There are direct punches, and hooks. Hooks can be thrown like upper cuts in boxing or like a swinger from behind. It is often used in a hidden way. The straight punches are also performed such as in Karate with horizontal or slightly twisted fists. The head and the back are taboo for punches.

There are 3 main kicks. The forward kick (like Mae Geri) is called “Tanjip”-kick, whereby the knee gets up high and the foot performs an arc from outside to the chest of the opponent(see image 13). This is also called the “Cobra”. In addition, I was introduced to the T-Kick, which resembles Yoko-Geri and can also be performed as 360-spinning kick. Often, the T-Kick starts from a holding position, one leg up (similar toTaekwondo). The kick is definitely quick and sharp. The third basic kick is called “Tampias” and looks like Fumikomi(inside kick). The athletes can stop the opponent with this cross-kick and continue with punches. The area of allowed contact is the whole leg, except the knee.

I realized that a lot of emphasis was given to leg and foot sweeps. The students demonstrated their techniques, which are take downs with a variety of scissor sweeps, whereby one hand touches the ground, and the other hands grabs the opponent before the legs close in (see images 14, and 15). Also, a full 360-sweep on the floor can take down the partner. Often combined with a kind of anaconda roll on the ground with crossed legs to spin the opponent. In the past, some accidents had been reported where athletes hit the ground with their head and suffered severe neck injuries.

Before the fight starts it is mandatory to perform a “dance”. This dance is probably easiest to describe as a mini-form which looks like a short Kungfu-performance. Every school has its signature moves, some may stand on one leg in a certain fighting posture, while others have an open hand form (see image 20). Anyway, it looks very elegant, like a traditional Balinese dance. These dance moves resemble the concept of Bakti Negara in memory of the oppression of martial arts during the colonial period up until the early 20thcentury. Historically, the Pencak Silat fighters had combined traditional music and dance movements to disguise the practice of their martial arts from the administration of the occupiers.

Also, during the regular competition there is almost no jumping around as we see it in Karate sport. However, the athletes here also move lightning quick. Their standard position would be a standoff almost like in Judo, with a wider stance like Shiko Dachi and with open hands; mainly one hand as fist and the other hand is kept open.

Open hand techniques

Master Adi and Master Oka demonstrated a variety of basics and applications of open hand techniques. Since Pencak Silat and the Balinese Bakti Negara are deeply rooted in the resistance movement, which required fighting hand to hand against armed enemies, the techniques had to be very efficient. Open, flat hands are used to stab the eyes and clap against head and ears, called “sword hands”. Another open hand technique is applied to grab and squeeze the throat in a low stance. This is called “the monkey grabs the fruit” and can also be applied to the groin. A double hand chop to the arterial parts at the neck is called “the closing lotus”. Spreading the arms in a circular way before the body (similar to Mawashi Uke) for the purpose of pushing or defending, is called “the lotus opens”. I don’t recall the poetic name for another technique, which Master Oka seemed to like very much, since he enjoyed a couple of times lifting me up on his shoulder and helicopter me around before slamming me to the floor (which he did gently).

Weapons

My specific interest for the journey was to learn about the different weapons in Silat. I thought about Karambit, Tekpiand the staff. However, to my surprise I learned that those are not known included in their system. I was explained that names for similar weapons might differ from island to island. Balinese schools train with various weapons, which in total might be up to 100 different weapons due to their different makeshift. Here in Ranting, a number of 9 weapons form the system of their martial arts. The most iconic weapon is the “Trisular”, trident pole (to be compared to as Sai), also known as Shiva’s weapon (part of the 3-wepaon symbol of Bakti Negara); the “Golok”, a knife/machete with 40 cm long blade (sharp on one side, see image 16)., “Kris”, the most sacredweapon, is still used for ceremonial purposes (see image 17); the “Toya”, a rattan staff, the size of a regular Japanese Bo-staff; “Tombak”, a bamboo spear, sharpened on one end (also part of the symbol of Bakti Negara); “Kipas”, a hand fan; “Pecut”, an over 2m long leather whip; “Celurit”, a sickle to cut rice and grass, such as Japanese Kama; and the classic Nunchaku, same as in Japan. However, the chain seems longer. There are also variations such as a 3-sectional staff.

There are also form competitions (like Kata). The forms are universal and basically set for the standard weapons across Bali. The practitioner must perform 3 forms after each other without any break. This is a total of 4 minutes performance!Walking into the arena with 2 weapons, the Golok (machete) in one hand, the long Rattan staff behind the back, the athletegreets the panel of referees and puts the Bo and the Golok on the floor. Then the open hand form starts, such as Kata in sports-karate, followed by the Golok, the machete, and at the end – without any break, the Bo-staff, Toya follows. This can also be performed by a team of two, which includes freestyle applications like in team kata (Bunkai).

The rattan staff is very light, and the practitioners move the staff easily and sometimes hit the floor with a loud bang. There is no “kiai” though. Breathing is important as it is meditation. Also, before the training everyone has a moment of meditation.

The movements with Golok, the machete, or rather a long-bladed knife is almost artistic. Fast circular movements from the wrist, long lounges with arms, cutting and spinning the knife across the back of hand looks fantastic. I have seen many villagers in the rural areas carrying such a long knife in their traditional garment on a daily basis (see image 18).

The Kris is considered a sacral, ceremonial weapon, often handed down from the father to the son (see image 17). The weapon is ca 40 cm long and has an ornament-rich scabbard made from bone. The handle is short and not straight. Just like the Golok, the rear end falls to the side like a beak, which would be carved with motifs. The blade is very interesting. It is curved and sharp on both sides. The blade also carries ornaments engraved. The specific snake form of the blade is symbolic for the Hindu culture and the way of life, moving towards the tip of life/knife. Every curve of the blade has a religious meaning. The practical use of the weapon would lead to more severe injuries than the Golok. If an opponent would be stabbed to the stomach, the blade would rip out intestines. This is not a weapon supposed to be worn every day. If there is an official ceremony, requiring the Kris to be part of the etiquette, the owner shall practice fasting for one month.

After 1 month and 7 days he can eventually carry the Kris. Every 6 months, the personal Kris must be consecrated again with a ceremony for praising spirit, mind, and heart of the owner. As far as the practice with Kris, there are training weapons, which are used in almost the same way as the Golok. At the beginning of the Kris form (kata) the weapon is held vertical and with a quick upwards movement the scabbard is catapulted into air and should be caught immediately. Not always easy, as I can confirm when I practiced.

I have to admit that for me, the most impressive tool of the system was the Pecut. This whip is about 2 m long, with a firm handle made of black braided leather. The end of the Pecut has a thin string of different material with a few knotson it. Even here, the number of knots is of traditional and ritual importance, referring to the Sanskrit. However, when Master Oka beautifully performed a “kata” and cracked the whip in my direction, the supersonic sound, created through the highspeed movement of the knotted string, gave me chills(see image 19). The weapon is so fast that you can’t see the string flying. The noise is scary, and the injuries would be terrible. The knots would penetrate the skin and slice the muscle. Good practitioners can aim precisely for an eye, ear, or the hand. Master Oka controls the space by walking like a Balinese dancer and cutting of the lines of the opponent. For sure, I had to try. With a bit of luck, I snapped the Pecutproperly at the first try and the sound was loud under the metal sheet roof. However, after a couple of more attempts, I realized that the end of the whip always touched my head on the way forward, which was a painful smack. I can only express my greatest respect to the master to be able to control such a dreadful weapon.

About belts in Bakti Negara

Bakti Negara has a grading system which is aligned with age, years of training, and skills. Colored belts are red, blue, yellow, and purple. Each level requires constant training of 18 months (3 level, each 6 months). The masters carry a black belt. However, the leader of the system, which is currently Master Ida Bagus Oka Dewangkara, who is awarded with the highest belt: a white belt. Correct, the top rank – and there is only one person at a time – is white.

Master Oka demonstrated how the Bakti Negara belt is supposed to be worn. The belt is made of soft material, just like the uniforms and it resembles a traditional belt of the sarong. However, the belt is shorter than Karate belts and is wrapped around the waist, with a knot on the right-hand side. No embroideries on the belt. The belt is done in a way that an upwards loop is created on the right-hand side. Despite being tight, one can just pull the loop and release the belt quickly, which eventually turns into a weapon. I was seized to feel the action of self-defense with the belt. Similar to the whip, one can catch the hand, wrap it around the neck or limbs. Also, the nasty whipping snaps are part of the applications.

Master asked, what happens if you have no belt? He said, you can use your t-shirt. So, his shirt came off and the same applications was demonstrated, wrapping it around a hand or blade. Very important is the movement of the defender, cutting of lines and observing the weak hand, which would be the direction to move.

Essentially, I saw the connection between whip, belt, and t-shirt, or any other availabilities.

Bakti Negara – more than a national sport

I was explained that about 60 % of the Balinese population train or have trained Bakti Negara. Also, on Java and other provinces is the number of practitioners in that range. With a population of 275 million people, Pencak Silat is practiced by Millions of people. Bali has 4.4 million inhabitants.

This can only be achieved through free access to training, inclusion into the school and afterschool curriculum, government support, and the religious component, embraced in the daily life of the Hindu population, as this is the majority on Bali. Indeed, there was no festival, no hotel event, tourist beach celebration or national parade without Pencak Silat.

The philosophy of Bakti Negara: Self-protection, protection of the family, protection of the nation, is still a living and existing concept of life. Only by looking at the deep connection between the history of Bakti Negara as tribal art, the value of a national identity, the practiced religion, and the shared responsibility for society, one can understand how Bakti Negara, like other Pencak Silat, is part of national DNA.

This makes a difference to most other existing martial arts or fighting sports. In my opinion, this can only be compared to the ancient concept of Budo, which however, is not a living mainstream philosophy anymore in Japan.

Final thoughts

I came to Bali to learn some techniques and get a better understanding for their martial arts. I was surprised to see the basic conditions for their training, which can’t be compared to those in Western countries. Despite, Master Adi and Master Oka and their students welcomed me and shared their time and friendship. They trusted me despite being a stranger and non-practitioner of their art. They also patiently endured all my questions and accepted my limited understanding about Balinese history and culture. I learned more about the people and the meaning of Bakti Nagara to society. I saw super talented athletes and friendly Masters which gave me a great opportunity to come into their house and train together – also under the protection of a pantheon of Hindu gods. The way of life on Bali is heavily influenced by the Hindu-religion and its philosophy; one should always try to achieve balance in life, family, work, nutrition, and any other activity.

I can only encourage the reader to look up videos and information about Pencak Silat competitions and practice.

Arya had set up a WhatsApp group and we began sharing photos and videos from the training. The morning after the last training day I moved further north to a remote area with plenty of rice fields and small villages, close to the mountain Gunung Batukau (2276 m), away from traffic and busy beaches. Here, I had time to relax and digest the time with the masters and practitioners of Bakti Negara (see image 21).

Few days later, before submitting this article, I received another invitation of Master Adi. The night before my departure from Indonesia he and his family came by to my hotel in Denpasar. They presented me with one of his personal Goloks (see image 22). What a great gesture. I will take home this fantastic gift, and much more importantly, great memories. I hope there will be another opportunity to meet.

I came to Bali as visitor and tourist and surely leave as friend. I will always remember Bakti Negara, Indonesian Pencak Silat, and the wonderful people of Bali.

Makasi (thank you), sampaj jumpa (Goodbye).

Disclaimer: Please consider this article as a travel report. Under no circumstances this article is meant to be a detailed account of Pencak Silat. My description is based on the exchange of information and interviews with local masters of the art and there might be misinterpretation of information on my side. Any comments or corrections are welcome.

Seneste kommentarer